Social media has proven its worth in the COVID-19 crisis.

Have we seen its potential reached in higher education?

About the author

Isobel Edwards prepared this article for a CIPR Professional PR Diploma assignment while studying with PR Academy

University communities are set to become increasingly fragmented in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. Social media will be key for PR professionals to build a lasting sense of togetherness.

The scene opens on four eggs nestled in egg cups on a simple wooden coffee table. As the iconic drum sequence of Queen’s ‘I want to break free’ kicks in, the viewer is held in a state of mesmerised suspense.

Will the eggs spontaneously smash? Hatch? Worse? After an agonising twenty-one second wait (an astonishing amount of time for users habituated to mindless scrolling) one egg reveals itself to have been the shiny bald head of a middle-aged man, enthusiastically launching into song.

Such is the simplistic joy of TikTok.

The iconic TikTok hit now has over 340,000 views on YouTube and numerous spin-off versions on the platform itself.

Launched on the international market in 2017, the app, which enables users to lip sync short video clips, now has 800 million active users worldwide. Such a stratospheric rise to the top can be attributed in part to TikTok’s popularity among young people, who are social media’s most intensive users. However, it seems unlikely that the app would have seen such a meteoric rise if 2020 had been a normal year.

Indeed, it is no exaggeration to hail TikTok as a saviour for many people during the UK’s national lockdown earlier this year, rapidly building a community of followers looking to fill their days at home. A dedicated community at that, as users spend an average of 52 minutes per day on the platform. Imagine what PR teams could achieve if we had our stakeholders’ undivided attention for 52 minutes per day.

The rise and rise of social media

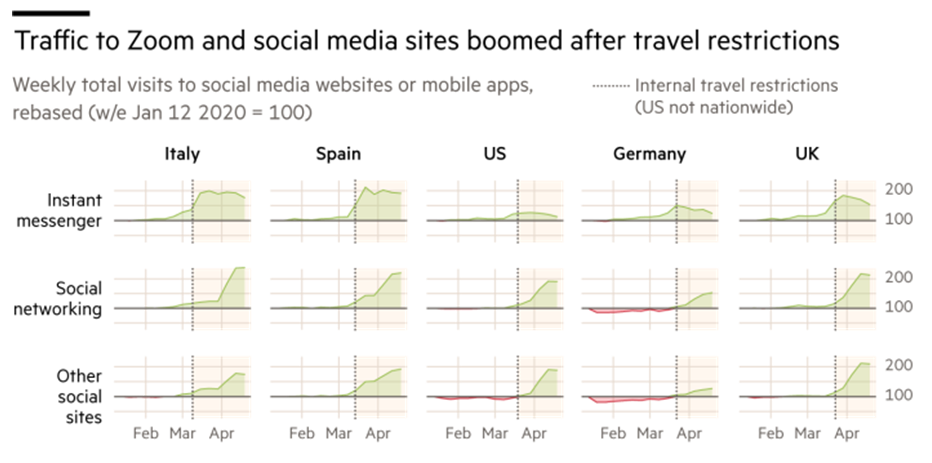

TikTok may be the standout contender, but it was not the only beneficiary of a public in national lockdown. Unsurprisingly, government limitations on face-to-face interaction prompted an unprecedented peak in social media use in Spring 2020.

Source: The Financial Times

Source: The Financial Times

This level of engagement may not be sustainable, but it does provide a wake-up call to PR practitioners: view social media as just an add-on at your peril. Individual platforms come and go, but it is safe to say that social media in some form is set to be a permanent, and increasingly significant, part of the PR landscape.

It is not just COVID-19 that has prompted this change: shifts in student behaviour and their expectations of their institution were well underway before the word ‘furlough’ had entered the common vocabulary. The way organisations interact with stakeholders has seen marked change ever since Millennials began shaking up traditional organizational hierarchies, flattening top-down systems to create more agile, autonomous teams and workers. In an organisational ideology where everyone is equal and anyone has access to anyone else, social media becomes the ultimate town hall.

Stakeholders who would previously have called up customer services to find information or register a complaint are now doing so directly (and very publicly) to organisational social media pages. Senior leaders that could previously have hidden behind their PR team are now expected to be open, accessible and able to justify their actions to an increasingly discerning public.

According to Ofcom’s latest Media use and attitudes report, 93% of 16-24 year olds now have a social media profile. The dominance of social media in PR practice has thus been coming for a while, but the events of 2020, from the COVID-19 pandemic to Black Lives Matter protests, have increased the urgency for a space where organisations can speak directly to their stakeholders and where stakeholders can feel genuinely heard.

Far from being impassable or exempt from these fluctuations, universities must take heed if they wish to hold their share of influence in the public sphere. The ivory tower is crumbling: we may speak optimistically of a return to ‘normal’, but it is unlikely that university communities as we know them will ever be the same again.

Faced with the possibility of indefinite flexible and blended learning models, how will universities unite a student body that may miss out on the usual bonding rituals of freshers’ week, orientation and the queue to be let into the lecture theatre?

Social media in higher education: looking beyond marketing

High praise aside, even the most innovative PR team may well hesitate before jumping on the TikTok bandwagon. It is hard to imagine where a university’s place would be among viral videos and six-month transformations.

At this point, communications teams might typically lose interest: if we can’t exploit the platform for our own messaging, what more does it have to offer? However, TikTok’s success in creating a sense of togetherness seems particularly enviable in a sector that looks set to be disparate for the foreseeable future. Even if we hold off creating an account, there are lessons to be learned from what the platform has achieved.

Consider, first of all, how the role of Social Media Officer is viewed in your organisation – that is, if you are fortunate enough to have a dedicated team member for the role. If they are to be found in Marketing, are they at risk of tunnel vision when it comes to setting goals for the platform?

Of course, social media has a key role to play in recruitment, especially when it comes to what researchers at Swansea University have termed ‘Electronic Word of Mouth’. Persuasion theorists have long remarked on the value of word of mouth recommendation, but the research suggests that this can be equally effective via digital channels. Indeed, the most recent New Applicants Survey from UCAS Media found that 89% of students who engaged with Unibuddy, a social platform connecting current students with applicants, felt more confident in going to university.

But should social media content creators be satisfied with getting students through the door? Before COVID-19, the logic of focusing social media resources on recruitment was perhaps more sound: engage prospective students from all over the world from a distance in order to physically persuade them onto campus, then continue the conversation via email, face-to-face meetings and on-campus activities.

Now though, faced with a cohort of students who may never enter the physical campus, it is time to get creative in how we build our university community.

Community is an abstract noun

What do we mean when we talk about community in the context of higher education, and what role do PR professionals have to play in its development?

The Cambridge Dictionary now offers a specialized internet and telecoms definition of community:

‘On social media, a group of people who have similar interests or who want to achieve something together.’

In the literal sense, universities are fortunate to have a ready-made community of students in the form of a new cohort each year. However, this will not add much value for students or for the institution unless significant effort is put in by PR teams to help it thrive.

Social media growth experts will advise consistently posting quality content as the way to garner engagement. This is no doubt part of the puzzle, but communities are not built through the gradual sedimentary build-up of pre-prepared, megaphone-style broadcasts from the organisation. Just as PR theorists have widely acknowledged the limitations of Shannon and Weaver’s early ‘transmission’ model of communication, they have recognised social media’s true potential to be as a method of cutting through the noise and creating what influence expert Philip Sheldrake describes as ‘human to human’ conversations.

In Share This Too, the seminal social media handbook from the Chartered Institute of Public Relations, Dom Burch argues that ‘natural and meaningful’ conversations on social media should mimic those in real life: ‘They are two-way dialogues, not one-way broadcasts.’ These conversations, he argues, become more meaningful as the relationship develops.

In this environment, the PR professional finds herself more often than not in the role of facilitator and listener as opposed to broadcaster.

Vehicle or destination?

When pitched alongside tangible outcomes such as placing a press release or recording a student testimonial, social media can feel like shouting into a black hole, especially when external signs of engagement, such as likes and comments, remain low.

For this reason, PR teams may fall back on using social media as a signpost: the vehicle through which they guide stakeholders to other channels, such as the news page of the website or recorded webinars. In this case, social media engagement may actually be high when measured in terms of click throughs, but the true potential of the platform is overlooked.

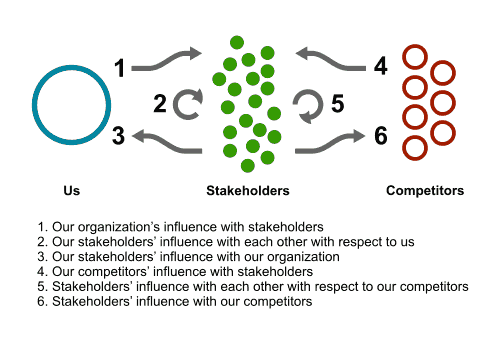

We now know that an organisation’s relationship with its stakeholders is far more complex than call and response. Once again, Sheldrake comes to the rescue, identifying six influence flows that exemplify the myriad and indirect ways in which a stakeholder may interact with an organisation.

Sheldrake’s Six Influence Flows. Image source: WADDS Inc blog

Sheldrake’s Six Influence Flows. Image source: WADDS Inc blog

At its most basic level, social media operates as a transmission tool, effectively managing an organisation’s influence with stakeholders and its stakeholders’ influence with the organisation. We see this all the time on institutional social media platforms: messages are published by PR teams and responses from stakeholders are received in the form of likes, comments or private messages.

But what if we as PR professionals set out to achieve more than this? If we can lean into the conversational nature of the platform, knowing when to listen and when to speak, we can begin to cultivate those meaningful relationships discussed by Burch. As the Arthur W. Page Society highlight in their report on The Authentic Enterprise, these relationships do not even have to be about us, but about nurturing connections among our stakeholders.

It can be as simple as setting up interest groups and allowing stakeholders to run with them, acting as moderator rather than leader. It can be as simple as Middlesex University creating an Instagram filter to celebrate its new cohort. It can be as simple as just listening (ASDA famously practised active listening on its channels for a full year before deciding how best to move forward with social media).

When we consciously adopt the role of facilitator in social media spaces, we offer up ways for the other influence flows identified by Sheldrake to take form. We allow our stakeholders to interact with each other with respect to us and our competitors, without needing to dominate such an exchange. We create a space in which genuine conversations can take place and are able to offer a listening and advisory ear within that. The goal is not to befriend our stakeholders, nor is it to manipulate them, but to be honest, humble and approachable.

Too often, social media is viewed as a means to an end, rather than the end in itself. In order to use the platform as a place to build a human to human community, it must be allowed to develop into a destination in its own right.

When we cease viewing social media as the distance to cross between the university and its stakeholders and start viewing it as the living relationship between the two, the true potential of the platform becomes apparent.

Just as TikTok has inspired its 800 million fans with the simple joy of the everyday, social media can be the place, not the signpost, for something meaningful.