The word search is perhaps the lowest form of puzzle. As a staple of Highlights magazines and family-restaurant placemats, its purpose is to use up time, quietly. Stare at a grid of letters and find, amid them, a list of indicated words. Is this fun? It is not. The word search is paperwork, but for kids.

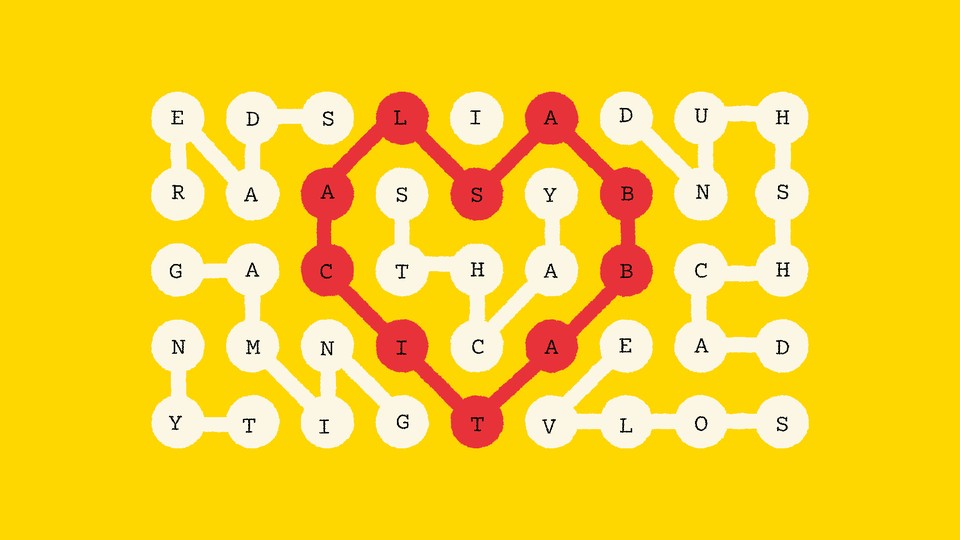

Over the years, many have tried to improve the puzzle, to make it more mature. Boggle, introduced in 1972, made word search competitive. SpellTower, a 2011 smartphone game, made it strategic. And now this week, The New York Times has put out Strands, the newest product in its games empire. Strands adds two new features to the classic place-mat game: The player must guess the words to find in each scramble based on a cryptic theme, and the scrambled words, which can bend in any direction, are arranged to use up the entire letter grid. These changes may not sound so transformational, but in the context of a word search, they’re a revelation. Many of the best games succeed by offering a novel take on something familiar. Strands does exactly that.

The new game is still in beta, which means you won’t yet find it in the Times’ games app, only on the web. The Times will kill off a game that doesn’t work, but if Strands survives the test, it will join a growing group of successful older siblings: Spelling Bee, Wordle, Connections, and, of course, the crossword. With these, the Times has single-handedly recovered the genre of low-stakes games that used to thrive in daily newspapers. In doing so, it has brought back a gentler philosophy of game design: that great joy can come from solving little problems on the regular.

Not so long ago, newspaper puzzles seemed on the verge of extinction. As I argued with my colleagues Simon Ferrari and Bobby Schweizer in our 2010 book, Newsgames, the print media had made the very strange decision to cede a large market for daily puzzling to mobile-game developers such as PopCap, the maker of Bejeweled. Newspapers, we observed, had forgotten that readers needed to be welcomed into the daily news—which is mostly bad news. A friendly and comforting ritual would do the trick: the sports, the weather, the comics, the crossword. But companies like the Times had not yet bothered to translate that function effectively from print to web (or app), so others had taken it from them—and made billions of dollars. The news business got Candy Crushed.

Now that trend has been reversed. The Times’ revival of newspaper games, which really took off with the acquisition of Wordle in 2022, has helped bring in huge amounts of premium-subscription revenue, according to the company. Jonathan Knight, the paper’s head of games, told me that tens of millions of people play Wordle every week, and almost half as many play Connections. Success for a newspaper game, to Knight, means players “coming back to it every day.” The ritual is the thing.

When Wordle first appeared, I analyzed the game in hopes of understanding what made it so compelling. The secret, I suggested, was that once you’d gotten even a couple of letters, the solution space narrowed quickly. And yet, because players don’t know how few words in Wordle’s dictionary might match the pattern before them, they could still feel extremely clever when they were able to home in on the final answer. This is why Wordle is delightful—and why the game is a terrific newspaper puzzle: You can start your day with it and feel smart and capable.

I still play Wordle daily, but I no longer reliably enjoy it. I’ve sometimes felt like the game is trying too hard to bamboozle me. Wordle can perform trickery in only one way: by including the same letter more than once. Because the game offers no explicit clue to repetition, you can easily overlook solutions that involve one. I felt this acutely this past Sunday, when it took me five guesses to get to STATE, the day’s answer, after having burned two on STAGE and STAVE. “These Times bozos,” I muttered to myself. “They’re ruining Wordle.”

But were they? I performed an analysis of Wordle’s daily solutions to find out. Ten of the words in February of this year had two of the same letter, but there were only six in January; back in February 2023, the game had 12. The game hadn’t changed—only my perception. If I was keyed into the idea that the Times might be trying to mislead me, perhaps this was on account of its latest hit, Connections. That game, released in the fall, presents a grid of 16 words; the player gets four tries to sort them into categories. For example, SHOUT, SNAP, WAVE, and WHISTLE are all “ways to get attention,” according to last Sunday’s puzzle. To increase the challenge, Connections throws in red herrings, words that are meant to deceive you because they might have an association with more than one group.

Wordle words are curated, but the game is just the game. Connections is different: It has a human author. And human authorship means that some specific individual—her name is Wyna Liu—is responsible for the game’s delight. Or for its suffering. Some Connections categories are nifty, and satisfying to identify. Others are so tenuous that you might never guess them on your own. For example, BASSINET, CELLOPHANE, HARPOON, and ORGANISM are “Words beginning with instruments.” BOOK, CACTUS, HEDGEHOG, and SKELETON are “Things with spines.” CLUE, FROWN, MELLOW, and PREEN are all “Colors with their first letters changed.” The latter, in particular, had produced some angry blowback on the internet. “I love that one!” Everdeen Mason, the Times’ editorial director for games, told me this week, when I brought it up.

Many people take great pleasure from Connections. I do not. If Wordle makes me feel smart, Connections makes me feel stupid. It’s a Guess what I’m thinking puzzle, except you, the player, don’t know anything about the mind whose thoughts you are guessing. Mason clarified that this is very much her team’s goal: “We want to make games where people can feel the person on the other side,” she said. But the authorial voice behind a given puzzle, whether it’s Connections or a crossword, can feel remote from the solver. Mason, who manages the team that makes the Times’ games, talked to me about a particular puzzle of Wyna’s, or of another editor named Joel; the app shows a byline credit for each one. But for outsiders, these names can feel like they refer to faceless puzzle overlords administering shrewdness from on high. The puzzle-maker risks coming across as better, smarter, and more clever than the rest of us.

In Connections, that feeling has a way of being amplified. You get to make only four wrong guesses, so you won’t have that much room for testing out solutions. When I asked the Times designers why players aren’t allowed a bit more leeway, Knight suggested that the four-guesses system matched the game’s “four groups of four” theme. “We tried three; we tried five; four just felt the best,” he said. The choice seemed arbitrary to me, and also punishing, but perhaps it’s wise to have at least one game in the app that’s easy to lose.

Connections does get less challenging the more you play, as its conventions and internal rules become apparent. Many categories are synonyms, for example, as are words that fill in the same blank for a set of common phrases. Crosswords are similar: They’re written in a secret language, and have a grammar that must be learned through repetition. This is not a flaw, or, not exactly. I play all of these puzzles even though they’re sometimes aggravating or arcane. I don’t love Connections, but I have great respect for its creators. After all, a feeling of frustration at one day’s crackbrained answers is intrinsic to the newspaper-puzzle genre. Perversely, getting mad about the puzzle can be part of the fun; it offers a common, lighthearted gripe in the family text chat. Tomorrow offers another shot at delight.

Strands, the new word-search game still in beta, seems to fuse some of the best features of Wordle, Connections, and the crosswords. The game might not be for everyone, but for me it represents a breakthrough. “We got really hyped about taking something classic—word search—and adding something new to it,” Mason said. Connections may torment its players with little room for error, but Strands rewards wrong guesses, in a way, by filling in a progress bar that gets you to a hint. The game displays its daily theme front and center, crossword-style, which helps you with the first, and toughest, word to find. From there, each further discovery shrinks the board and makes the next one that much easier, delivering a pleasant sense of acceleration toward victory.

With only three puzzles under my belt so far, I still find Strands intriguing. That sensation could wane—the game might be too easy—but for now, I’m interested. The game draws on a familiar format that everyone knows, and varies that format in a manner that is reminiscent of other games without being reliant on their mastery. It makes the player feel smarter than they really are. This is the purpose of newspaper games: to give players a reliable feeling of control, once a day at least, in a world that’s spinning out.