Artists Are Losing the War Against AI

OpenAI has introduced a tool for artists to keep their images from training future AI programs. It may not make a difference.

Late last month, after a year-plus wait, OpenAI quietly released the latest version of its image-generating AI program, DALL-E 3. The announcement was filled with stunning demos—including a minute-long video demonstrating how the technology could, given only a few chat prompts, create and merchandise a character for a children’s story. But perhaps the widest-reaching and most consequential update came in two sentences slipped in at the end: “DALL-E 3 is designed to decline requests that ask for an image in the style of a living artist. Creators can now also opt their images out from training of our future image generation models.”

The language is a tacit response to hundreds of pages of litigation and countless articles accusing tech firms of stealing artists’ work to train their AI software, and provides a window into the next stage of the battle between creators and AI companies. The second sentence, in particular, cuts to the core of debates over whether tech giants like OpenAI, Google, and Meta should be allowed to use human-made work to train AI models without the creator’s permission—models that, artists say, are stealing their ideas and work opportunities.

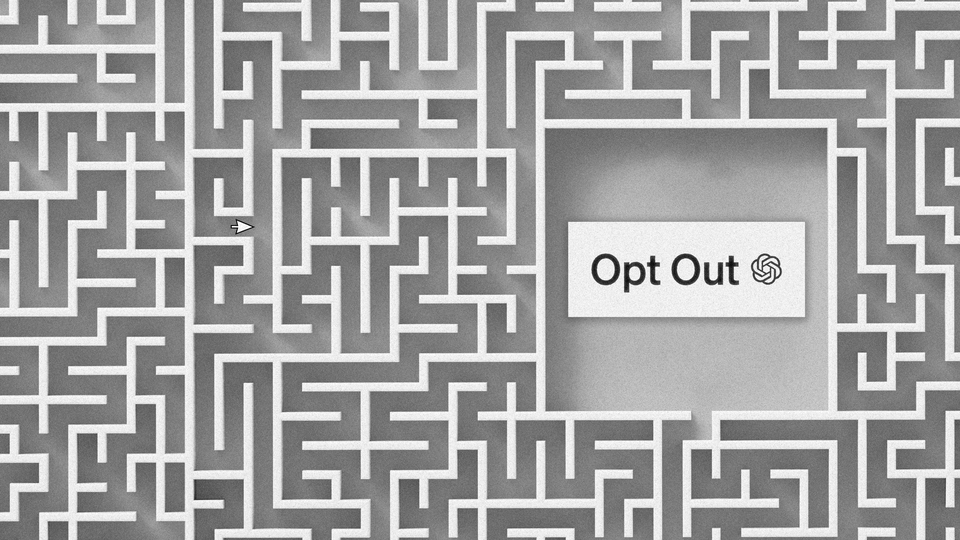

OpenAI is claiming to offer artists a way to prevent, or “opt out” of, their work being included among the millions of photos, paintings, and other images that AI programs like DALL-E 3 train on to eventually generate images of their own. But opting out is an onerous process, and may be too complex to meaningfully implement or enforce. The ability to withdraw one’s work might also be coming too late: Current AI models have already digested a massive amount of work, and even if a piece of art is kept away from future programs, it’s possible that current models will pass the data they’ve extracted from those images on to their successors. If opting out affords artists any protection, it might extend only to what they create from here on out; the work published online in all the time before 2023 could already be claimed by the machines.

“The past? It’s done—most of it, anyway,” Daniel Gervais, a law professor at Vanderbilt University who studies copyright and AI, told me. Image-generating programs and chatbots in wide commercial use have already consumed terabytes of images and text, some of which has likely been obtained without permission. Once such a model has been completed and deployed, it is not economically feasible for companies to retrain it in response to individual opt-out requests.

Even so, artists, writers, and others have been agitating to protect their work from AI recently. The ownership of not only paintings and photographs but potentially everything on the internet is at stake. Generative-AI programs like DALL-E and ChatGPT have to process and extract patterns from enormous amounts of pixels and text to produce realistic images and write coherent sentences, and the software’s creators are always looking for more data to improve their products: Wikipedia pages, books, photo libraries, social-media posts, and more.

In the past several days, award-winning and self-published authors alike have expressed outrage at the revelation, first reported in this magazine, that nearly 200,000 of their books had been used to train language models from Meta, Bloomberg, and other companies without permission. Lawsuits have been filed against OpenAI, Google, Meta, and several other tech companies accusing them of copyright infringement in the training of AI programs. Amazon is reportedly collecting user conversations to train an AI model for Alexa; in response to the generative-AI boom, Reddit now charges companies to scrape its forums for “human-to-human conversations”; Google has been accused of training AI on user data; and personal information from across the web is fed into these models. Any bit of content or data points that any person has ever created on the web could be fodder for AI, and as of now it’s unclear whether anyone can stop tech companies from harvesting it, or how.

In theory, opting out should provide artists with a clear-cut way to protect a copyrighted work from being vacuumed into generative-AI models. They just have to add a piece of code to their website to stop OpenAI from scraping it, or fill out a form requesting that OpenAI remove an image from any training datasets. And if the company is building future models, such as a hypothetical DALL-E 4, from scratch, it should be “straightforward to remove these images,” Alex Dimakis, a computer scientist at the University of Texas at Austin and a co-director of the National AI Institute for Foundations of Machine Learning, told me. OpenAI would prune opted-out images from the training data before commencing any training, and the resulting model would have no knowledge of those works.

In practice, the mechanism might not be so simple. If DALL-E 4 is based on earlier iterations of the program, it will inevitably learn from the earlier training data, opted-out works included. Even if OpenAI trains new models entirely from scratch, it is possible, perhaps even probable, that AI-generated images from DALL-E 3, or images produced by similar models found across the internet, will be included in future training datasets, Alex Hanna, the director of research at the Distributed AI Research Institute, told me. Those synthetic training images, in turn, will bear traces of the human art underlying them.

Such is the labyrinthine, recursive world emerging from generative AI. Based on human art, machines create images that may be used to train future machines. Those machines will then create their own images, for which human art is still, albeit indirectly, a crucial source. And the cycle begins anew. A painting is a bit like a strand of DNA passed from one generation to the next, accumulating some mutations along the way.

Research has suggested that repeatedly training on synthetic data could be disastrous, compounding biases and producing more hallucinations. But many developers also believe that, if selected carefully, machine outputs can rapidly and cheaply augment training datasets. AI-generated data are already being used or experimented with to train new models from OpenAI, Google, Anthropic, and other companies. As more and more synthetic images and text flood the web, that feedback loop—generation after generation of AI models passing on patterns learned from human work, regardless of the creators’ permission—could become inescapable.

In the opt-out form released last month, OpenAI wrote that, once trained, AI programs “no longer have access to [their training] data. The models only retain the concepts that they learned.” While technically true, experts I spoke with agreed that generative-AI programs can retain a startling amount of information from an image in their training data—sometimes enough to reproduce it almost perfectly. “It seems to me AI models learn more than just concepts, in the sense that they also learn the form such concepts have assumed,” Giorgio Franceschelli, a computer scientist at the University of Bologna, told me over email. “In the end, they are trained to reproduce the work as-is, not its concepts.”

There are more quotidian concerns as well. The opt-out policy shifts the burden from ultra-wealthy companies asking for permission onto people taking it away—the assumption is that a piece of art is available to AI models unless the artist says otherwise. “The subset of artists who are even aware and have the time of day to go and learn how to [opt out] is a pretty small subset,” Kelly McKernan, a painter who is suing Stability AI and Midjourney for allegedly infringing artists’ copyrights with their image-generating models, told me. (A spokesperson for Stability AI wrote in a statement that the company “has proactively solicited opt-out requests from creators, and will honor these over 160 million opt-out requests in upcoming training.” Midjourney did not immediately respond to a request for comment, but has filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit.) The same could be true of an author having to separately flag every book, editorial, or blog post they’ve written.

Exactly how OpenAI will remove flagged images, or by what date, is unclear. The company declined an interview and did not respond to a written request for comment. Multiple computer scientists told me the company will likely use some sort of computer vision model to comb through the dataset, similar to a Google Image search. But every time an image is cropped, compressed, or otherwise edited, it might become harder to identify, Dimakis said. It’s unclear if a company would catch a photograph of an artist’s painting, rather than the image itself, or that it would not knowingly feed that photo into an AI model.

Copyright and fair use are complicated, and far from decided matters when it comes to AI training data—courts could very well rule that nonconsensually using an image to train AI models is perfectly legal. All of this could make removal or winning litigation even harder, Gervais told me. Artists who have allowed third-party websites to license their work may have no recourse to claw those images back at all. And OpenAI is only one piece of the puzzle—one company perfectly honoring every opt-out request will do nothing for all the countless others until there is some sort of national, binding regulation.

Not everyone is skeptical of the opt-out mechanism, which has also been implemented for future versions of the popular image-generating model from Stability AI. Problems identifying copies of images or challenges with enforcement will exist with any policy, Jason Schultz, the director of the Technology Law and Policy Clinic at NYU, told me, and might end up being “edge case–ish.” Federal Trade Commission enforcement could keep companies compliant. And he worries that more artist-friendly alternatives, such as an opt-in mechanism—no training AI on copyrighted images unless given explicit permission—or some sort of revenue-sharing deal, similar to Spotify royalties, would benefit large companies with the resources to go out and ask every artist or divvy up some of their profits. Extremely strict copyright law when it comes to training generative AI, in other words, could further concentrate the power of large tech companies.

The proliferation of opt-out mechanisms, regardless of what one makes of their shortcomings, also shows that artists and publishers will play a key role in the future of AI. To build better, more accurate, or even “smarter” computers, companies will need to keep updating them with original writing, images, music, and so on, and originality remains a distinctly human trait.